To know the land is to love the land.

To love the land is to care for the land.

To care for the land is to live wisely with the land.

To live wisely with the land is to learn from the land.

To know the land is to love the land.

WRITTEN BY GUARINA LOPEZ

FEATURED IN GET RAD BE RADICAL ISSUE 02

We all do it. When we find something we love, we learn about it, we dig into it, and spend time getting to know everything about it.

We dedicate hours and days, and schedule our lives around it, so how can we learn to passionately investigate the places we go to do the things we love? And why should we?

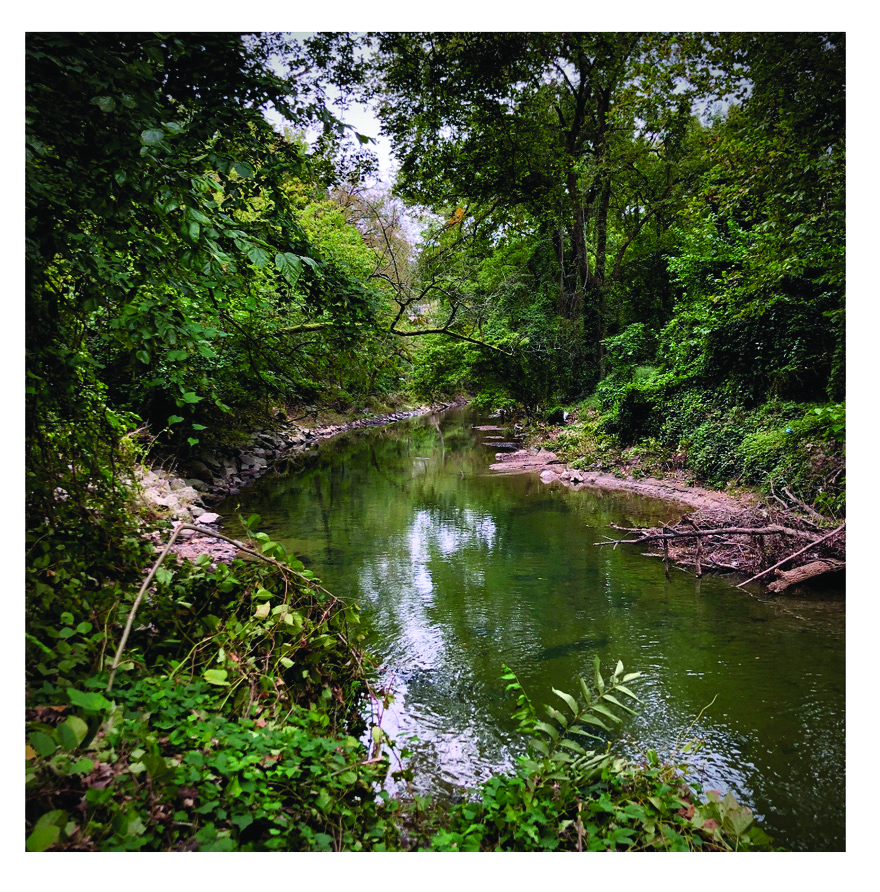

I love being on my bike, getting on the road, or the trail. I become suddenly filled with a sense of freedom that increases with the swiftness of my bike. But before I can get onto my beloved trail, I have to work my way through city traffic. My anxiety increases and I feel miles away from my connection to the land’s ecosystems. The land that brings me so much joy and nurtures my soul.

It is human nature to project our ideas onto a place to fulfill something missing in our lives. We imagine that natural landscapes will ease our worries or provide respite, but we forget how our very presence has impacted and reshaped these natural environments. To live with the natural world responsibly, I have to learn from it and about it, which means privileging nature above all else and learning to observe rather than assume.

This concept is not that different from how I was raised to respect my elders, not to talk but simply to listen, and by listening I began to learn. Nature is our elder and deserves infinite acknowledgment and respect.

Western culture teaches us to disassociate ourselves from the natural world. We have been given but two choices: to become civilized/ modern or to remain savage/wild. The understanding is that the “civilized” must develop separately from their natural ecosystems, claiming and declaring humans as the ultimate being and nature as the mute participant to dominate. To be “savage” means to exist in relation to the natural world and resist the Anthropocene.

Many of us exist somewhere in between these seemingly polar-opposite ways of being. I was raised both in the city and in the country. My tribe, the Pascua Yaqui, became an urbanized community, but we also have traditional villages in remote areas of the Sonoran Desert. We are a border tribe because the southern border between Arizona and Mexico effectively divided our communities. Before the colonial borders were erected, the Yaqui settled in present-day Arizona, California, and Colorado.

Today we have two villages in Tucson; the one I grew up with is now part of downtown and is flanked on one side by a freeway. We have coexisted with other tribes of the region and live most closely with the Tohono O’odham. The Yaquis received federal recognition in 1978 and are considered a sovereign nation within the so-called US, and an autonomous Indigenous community in Mexico. Our traditional name in our language is Yoeme, and in Spanish, it is Yaqui.

In many ways, I have lived simultaneously in the Indigenous world and within the non-Indigenous world. I have participated in my traditional ceremonies while living a totally “modern” life. During my youth in Tucson, I watched my dad grow a garden in the front of our house replete with apricot and fig trees, and a cactus garden in the back of the house with agave, sahuaro, and chollas. When we moved to northern New Mexico, we no longer had gardens but horses, a donkey named Pete, and more dogs than I can remember. I was introduced to a new ecosystem that included snow, monsoons, coyotes, arroyos, acequias, aspens, sage brush, and green chili. I met my half-sister, whose family is Taos Pueblo. I saw how other Native communities celebrated rites of passage and the change of seasons with their unique ceremonies, songs, and dances. They were different from our own, yet they felt familiar, probably because all our creation stories are grounded in our respective ecosystems.

To live with the natural world responsibly, I have to learn from it and about it, which means privileging nature above all else and learning to observe rather than assume.

To love the land is to care for the land

Each landscape I inhabited became a part of who I was at that point in my life. I can measure my growth and experiences alongside the seasons and topographical changes. In the beginning, I was a water creature born in the foggy mist of San Francisco, I became a little bobcat racing through the low mountains in the dry desert heat of Tucson. I then transformed into a coyote nibbling on pinon nuts at the base of the Aspens in Santa Fe. As an adult, living on the east coast on the ancestral territory of the Piscataway and Anacostan/Nanticoke, I have met humidity.… I’ll just leave that one there. I met rain, heat, and snow and loved them equally as only a child can do. With each move, I was introduced to new smells, different constellations, and ways of interacting with the landscape.

I didn’t ask the land to be my teacher, but that is how our relationship evolved. She has carried me through the seasons, through miles of running, and lured me onto her paths by bike. She has offered me silence and encouraged me to learn about her. The more I engage with the ecosystems of the places that bring me joy, the more compelled I am to protect and care for them, which is an example of being in good relations. Native people say ‘all my relations’ because we are engaging in relationships of reciprocity with all the beings around us.

To care for the land is to live wisely with the land

A lot of what this country teaches about the land stems from a colonial perspective. We’re getting hip to this and some people who are unlearning refer to it as decolonizing. The language of decolonization in today’s vernacular has extended this notion to include everything from the foods we eat to the words we use. In 2012 educators and scholars Eve Tuck and K. Wayne Yang wrote a paper titled ‘Decolonization is not a metaphor’ in which they state: “Decolonization brings about the repatriation of Indigenous land and life; it is not a metaphor for other things we want to do to improve our societies and schools.”

In their paper, Tuck and Yang boldly state that anything other than returning land to Indigenous people, thus recognizing their sovereignty, is not decolonization. Applying the term to other injustices is just another form of “settler appropriation”. This logic, of course, can be argued but what I appreciate about the finality of Tuck and Yang’s description is that it begins and ends with land back. Their definition of decolonization asserts that the only way forward is to return lands to Indigenous peoples thereby allowing Native communities to enact their specific forms of sovereignty within their communities. Once the land is returned, then other injustices that have plagued our communities can begin to be dealt with, such as food sovereignty and restorative justice, to name a few.

Native people say ‘all my relations’ because we are engaging in relationships of reciprocity with all the beings around us.

To live wisely with the land is to learn from the land

How does this relate to riding bikes? That’s easy; it relates if you want it to relate. I don’t want to sound glib, but this is where you, as a cyclist, can ask yourself how you want to relate to the land around you, that has given you so much. If you’re going to be a true co-conspirator to Indigenous people, you must want to learn about the land of your own volition.

What type of biome do you live in? Which plants, animals, birds, and fauna are indigenous to the region, and which are invasive? Which Indigenous people are ancestral to the region? Do they still live there? Why or why not?

Learning about the land and its history allows us to relate to it more meaningfully than through a purely extractive relationship. Learning about the history of the land disrupts the cultural amnesia of the American psyche, whose entire narrative is based on the idea that Indigenous people were and still are the inevitable cost of American progress. Colonial history portrays the land as something to be possessed while simultaneously eliminating Indigenous oral histories. Land possession and historical narratives work in tandem to dispossess Native people of the connection to this content. This declaration of complete erasure is how we got to where we are today.

So, how can you begin to shift your relationality to the land around you?

Start by understanding these basic but necessary facts:

- All land in the so-called US is Native land.

- Public lands, like the National Parks and Forests, were taken via theft and broken treaties.

- Settlers described this continent as “wilderness” invalidating the unique land practices cultivated by Indigenous people since time immemorial. Upholding the concept of wilderness frees people from the responsibility of US imperialism, genocide, land theft, climate change, and environmental injustices

- Indigenous science is science. Traditional ecological knowledge is valid and, when reintroduced, helps return ecosystems to their natural abundance, cycles, and rhythms.

- Indigenous languages draw from their unique ecosystems.

- Returning the land means promoting language revitalization.

- Protecting the land means maintaining language sovereignty.

- Federally recognized tribes are sovereign nations; we adhere to our own legal systems based on customary law and constitutional law.

- No two tribes are the same. There is no pan-Indigeneity. Currently, there are five hundred seventy-four federally recognized tribes and more than sixty state-recognized tribes.

If you love the land, then you must acknowledge the land

I want to shift the meaning of a land acknowledgment from a literal statement of whose land you currently occupy to acknowledging the land and what that responsibility entails. In the past year, I have seen many US institutions and individuals scurry to figure out what a land acknowledgment is, who should do it, how to do it, and when to do it. I am not here to tell you how to do it; that is still on you. Instead, I am interested in delving a little deeper into the why, so that you as a non-Native person can understand the depth of committing to this action and that you retain what really matters-a true unbiased understanding that all of the so-called US is Native land, always has been, and should rightfully be returned to us in due course.

Unlearning is a lifelong process but part of committing to unlearning means sitting with the uncomfortable truths. So if figuring out how to do a land acknowledgment is difficult for you, I’m here to say that it’s much easier than being dispossessed of that land. For me, my bike is the connector to community, to land, and to activism. Biking is the conduit of change that has allowed me to enter into a relationship of reciprocity with the ecosystem I live in. If this resonates with you, it is your responsibility to be in good relation with the land, history, and Indigenous people.